RITUALISTIC SYMBOLISM OF EMBEDDED ECOLOGIES – KOLAM AND MANDALA

Dr. R.J. Kalpana Ph.D

The Trumpeter, University of Athabasca NOVEMBER 2008

The term mandala was used in Kautilya’s Arthasastra, book 61, to define the spatial configuration of the neighbouring kingdoms for the strategic benefit of kingly governance. In the Tantrik tradition, mandala refers to the space that is enclosed within a circumferential line and is often used to invoke the presence of a particular god in that space. The space is usually circular but can be a square or a semi-circle, a triangle or the shape of vulva, among others. 2 At a more generic usage of the word, mandala refers to its auspiciousness, hinting at the presence of something divine within the beautiful precincts of its pre-defined physical structure. A religious etymology appears in Kularnava-Tantra:

“mangalatvac ca dakinya yoginiganasamsrayat

Lalitatvac ca devesi mandalam parikirtitam// 3

“O, mistress of the gods, it is called mandala because it is auspicious, because it is the abode of the group of Yoginis of the Dakini, and because of its beauty.”

The various shapes and structures of the mandalas are based on the religious traditions of different schools, the gods propitiated, and the practitioner’s goal. Mandalas are prepared from various materials including coloured powders, precious stones, flowers, fruits and leaves. Keeping in line with the inherent philosophy of the mandala, it isn’t a mere spatial design but a terrestrial structure where divinity is invoked into in order to become part of the structure.

Mandalas are required in rituals and occasions of religious observances and initiation rites. At the time of the initiation, the mandala structure functions as a place where the invoked gods become visible to the initiate for the first time thereby confirming his initiation. 4

The mandala structure represents the pantheon of deities in a particular religious school and expresses the hierarchical order within the system. This hierarchy in turn is redefined to indicate a cosmic order as well.

Mandala is clearly defined by Pott who describes it as “a mandala as a cosmic configuration in the center of which is an image or symbolic substitute of a prominent god surrounded by those of a number of deities of lower rank ordered hierarchically both among themselves and in relation to the chief figures, which configuration may be used as an aid to meditation and in ritual as a receptacle for the gods.” 5

Mandalas are objects of temporary ritualistic use. The deities are invoked into them and dismissed at the end of the ritual, after which the mandala is dismantled. Mandalas are often constructed first by the drawing of the lines of the structure and the deities are invoked into them with mantras later.

According to Burnner, she distinguishes between four basic types of mandalas.6

Type 1: Limited surfaces without a clear structure, which are commonly used as seats for divinities during the ritual, such as cow-dung mandalas and are called ‘seat-mandalas.’

Type 2: Limited surfaces with geometrical designs prepared from coloured powders for temporary use. They are large sized and can allow the priest to enter and move around and are called image-mandalas.

Type 3: Limited surfaces divided into squares into which divine or demonic powers are invoked using food offerings and are called distributive-diagrams.

Type 4: The term mandala is used to designate the symbolic shape of the five elements and the planetary spheres. The five elements are used for purification rites.

Mandalas come in different shapes and forms and are made of various constituent parts. The most basic ones are those of the Lotus design and the square shape within which can be found various geometrical patterns.

The lotus in Hindu cosmology seeks to represent the Goddess of Wealth or abundance, Lakshmi. It is a symbol of creation, purity, and transcendence and is the sphere of the absolute. It is especially known as a symbol of the female reproductive organ. 7 It has been connected with the water symbolism since time immemorial.

The square grid mandala is obtained by drawing a certain number of vertical and horizontal base lines to form squares on the surface and is later filled with coloured powders or grains. In the centre is usually a lotus symbolizing feminine divine and on the outside is a square nested with three coloured lines of white, red, and black, signifying sattva, rajas, and tamas. 8 In addition, it also contains a phallic symbol within the lotus signifying the obvious fertility rites and of the cosmic creation in a larger sense. The idea of a cosmic divine is inseparable from the geometrical symbol.

A more simplified version of the mandala prevalent to this day in daily ritualistic usage in South India is called kolam or rangoli in North India. A new Kolam is created every day in a ceremonial gesture of beauty, gratitude, and sacrifice by the women of the household, said to be manifestations of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth. The daily practice of clearing the space by washing the sidewalk and creating splendour for all to see is a sadhana or spiritual practice through which we invoke divinity. The principles of Satyam-Sivam-Sundaram, truth, consciousness and beauty are at play in every facet of our lives and Kolam reminds us of this on a daily basis. Whenever we create beauty we are asking the goddess Lakshmi to bestow her blessings. Insects and birds feed on the rice flour used for drawing the traditional Kolam at the entrance of houses. Thus, the Kolam represents man’s concern for all living creatures. The Kolam and the bright red border or kaavi enclosing it are also believed to prevent evil and undesirable elements from entering the houses.

Practiced mainly in south India, kolam is the art of decorating patterns and designs in pooja rooms or prayer halls and courtyards. Done mainly by girls and women, a kolam is drawn on the ground or on a floor using the medium of rice flour, sandstone or limestone. This colourful tradition goes back to 2500 B.C. when kolams were drawn with coarse rice flour. Rice flour is seen as an offering to Lakshmi, who is the goddess of rice and wealth and who is believed to attract prosperity. The designs of kolams are fairly common throughout the country of India and consist of geometrical patterns of squares, circles and triangles, and designs of conch shell, leaves, trees and flowers.

Alpana or Rangoli is a humble yet very sacred art of India which is practiced daily as a ceremonial offering. No matter what circumstances one lives in, there is always room to bring more beauty and grace into the world.

Any one travelling through rural Tamil Nadu during the months of December and January will be richly rewarded by the sight of a variety of patterns decorating the courtyards of even the humblest of homes. These patterns are referred to as Kolam in Tamil and it is a general term for all kinds of decorations. In addition to being used as threshold patterns the same patterns are also used as tattoo designs and as decoration on the walls of rural houses. There are also certain patterns which are used as magical designs or yantras and such Tantric designs are also used in the puja or prayer room.

Kolam is the art of creating rice flour or chalk decorations or mandalas on a sidewalk, doorstep or wall. Some designs are simple, white, geometric patterns, covering little space, while others are large, elaborate works of art, incorporating many colours and portraying devotional themes.

Traditionally, different designs are prescribed for each day of the week. Mondays to honour Soma, Moon. The moon adorns Siva’s hair and is said to bring feminine grace and beauty as well as mental clarity. Tuesdays to honour Mars. It frees one from debts, poverty, illness and brakes the bonds of attachment. Wednesday to honour Mercury. It promotes intelligence and prosperity and brings the blessings of harmonious communication. Thursdays to honour Jupiter. It creates beneficial energies to bring wisdom, intelligence and longevity to all who see it. Fridays to honour Venus. It harmonizes the energies to bring wealth, prosperity and abundance is all aspects of one’s life. Saturdays to honour Saturn. It mitigates the hardships that this planet can create- such as delays, sorrow, restrictions and adversity. Sundays to honour Sun. It attunes the energies for the entire week and brings general well-being. These are the nine planets that are said to rule our lives and the lives of the cosmos and have to be propitiated for benefit of universal well-being. These nine planets are zodiacal representations in our astrological charts that have been studied since ancient times. The impermanent nature of these paintings is a metaphor for maya, the illusionary nature of life.

The traditional forms of the kolam patterns are taken from nature and are representative of its presence in our lives. The colours are also taken from natural materials. Some of the kolam patterns are atypical of the gods invoked akin to the mandalas.

The designs are symbolic of mandalas but as such no invocation rites are involved. They are mere representative of the deities called upon to bear witness to the occasion. On religious festivals they would then take on the additional spiritual significance and on such occasions, particular kolams, specific to the gods invoked are drawn.

Folklore has mandated that it is a sign of invitation at the entrance of the house that all are welcome to co-exist and eat harmoniously. The lines of the geometrical shapes must be completed so as to symbolically prevent any sort of negative energy entering into the domain.

To begin the day with the creation of the kolam in Hinduism is said to attune ourselves with the universe and validate our place within it. The kolams we see everyday during our travels are signs of Divine Providence. It is this pervasive sense of the sacred that characterizes India’s spiritual depth. People are careful when they walk, not to upset these diagrams, although they are not meant to be permanent. Like life, and wealth, they must constantly be regenerated, and in this way our faith in the Divine is constantly restored.

Kolams and mandalas are used to synthesize and integrate our presence and experience into a vibrant whole. The basic motif is that of a central point within the psyche to which everything is related and is a constant source of energy. It is indicative of a symbolic journey that can lead us to inner peace and a deeper sense of universal interconnectedness.

The primal shape of the circle is the template of creation. It signifies that of unity and wholeness. It is the one principle that provides the foundation for all mathematical sciences. As such it is the perfect symbol of creation and inter-connectedness with nature. The core structures of embedded ecologies are a union of the male and female element at one level and at another level the inter-relation between nature and culture.

The embedded ecological symbols of kolam and mandala are profound representations of continuity, integration, and universal connectedness of beginnings and endings. It is definitive of the place of human beings in the cosmology. The relation between the unified field of existence and the collective unconsciousness is represented in such archetypal patterns. The casual relationship between the cymatic pattern and the Hinduism archetypal motifs exposes the essential pattern of the universe.

Biologist Rupert Sherdrake 9 suggests the theory of morphic-resonance, a vibrational archive of knowledge intercommunicating ideas, strategies and behaviours that each species has specific access to. He describes our bodies as ‘nested hierarchies of vibrational frequencies.’10

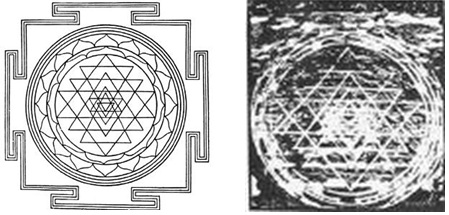

This is keeping in line with the ancient Hindu significance of the word Om. The consciousness, the unconscious, the in-between state and the entire physical phenomenon is represented within that word. The Absolute, the illusions, and the infinite universe are symbolized within Om. When we look at the most powerful of mandalas, the SriChakra and the pictorial image of the word Om captured through a tonoscope, we will find a marked similarity in the resultant images.

SriChakra Om Sound Through Tonoscope

The Vedic vision of the human body is a nest of hierarchical energies and the journey towards enlightenment is in physical terms raising the frequency of the chakras to the highest possible vibrations, which is a series of concentric circles at low frequency but becomes increasingly complex as the frequency increases. The ultimate goal of the Vedic philosophy is to reach a high state of vibrational frequency that one merges with the cosmos and attains a state of cosmic harmony.

The microcosm and the macrocosm hold the key to the understanding of the Hindu usage of embedded ecologies. The Cosmos is mirrored within the universe in the smallest of particles as is mirrored in the pictorial representations of kolam and mandala.

Effect of sound on water Kolam design

Encrypted within the collective psyche of the universe is the source of instinct, symbols, myth and archetype. This entangled conscious universe operating at the Planck scale is a unified field of intercommunication of the past and future. The ancients understood this to be metaphysical space of the astral or cosmic realm.

These embedded ecologies that Hindus use in their daily living demonstrate the morphology of the world and is a deliberate geometric description of the life-force. As shown in the above diagrams, ancient Hindus were well-aware of the geometry of sound. They understood quantum physics and concluded that the body and the Universe is a cloud of vibrating energy and that the secret of health and happiness is to keep those layers of energy in tune.

The immense space within the atomic structure confirms reality is holographic. The objects we consider real is all illusion.

“One day it will have to be officially admitted that what we christened reality is an even greater illusion than the world of dreams.” 11

The symbolism of human society reflects human consciousness, cryptography of spiritual attainment embedded within cultural ecologies. The anima-mundi, or the world-soul or collective consciousness contains the building blocks of organic life and all these embedded ecologies are but symbolic reminders that an archived morphology exists and each symbol is representative of a vibrating organizational intelligence.

In conclusion, I invoke the most powerful and most basic of the Isa Upanishad sloka:

“om purnamada: purnamidam

purnad purnamudacyate

purnasya purnamaday

purnamevavasisyate”12

The complete Cosmic Absolute has immense potencies, in which this material universe is but a temporary manifestation. The universe functions on its own time scale, fixed by the energy of the Absolute and when that schedule is completed, this temporary manifestation will be annihilated by the Absolute.

All facilities and faculties are given to the temporary manifestations of animate objects of creation, mainly humans, to realize the Absolute. The ritualistic symbolism of the embedded ecologies of the kolam and the mandala are but constant reminders to the humans of the Cosmic Absolute and the journey that they have to make to complete the cycle of oneness, in order to merge with the Absolute. And very like the kolam and mandala, the temporal nature is reflected in the cosmogenesis theory of annihilation and re-creation.

************

REFERENCES

- Kautilya, Arthasastra, 2003, Lexington Books

- Brunner, H. 1992 Jnana and Kriya: Relation between Theory and Practice in the Saivagamas. In Ritual and Speculation in Early Tantrisim. Studies in Honour of Andre Padoux. ed., T. Goudriaan. Albany New York: University of New York Press. P. 1-59.

- M P Pandit, Kulavarna Tantra, 1965, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass 17-59.

- Torzsok A.H.F., 1999, The Doctrine of Magic Female Spirits: A Critical Edition of Selected Chapters of the Siddhayogesvarimata (tantra), Oxford: Oxford University, p. 183-4.

- Pott P.H.1966, Yoga and Yantra: Their Interpretation and Their Significance for Indian Archeology. Trans., R Needham

Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, p. 71. - Brunner, H. 1986, Mandala et yantra dans le sivaisme agamique: Definition, description, usage ritual. In: Mantras et diagrammes rituals dans l’hindouisme. Table Ronde, Paris 21-22 Juin 1984, ed., A.Padoux, Paris: Editions du Centre national de la recherché scientifique 11-31.

- Gutschow. N. 1997, The Nepalese Caitya: 1500 Years of Buddhist otive Architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. Stuttgart/London: Axel Menges, p.248ff.

- Rastelli, M. 2000, The Religious Practice of the Sadhaka according to the Jayakhyasamhita. Indo-Iranian Journal 43:319-395..

- Rupert Sherdrake, 1995, The Presence of the Past:Morphic Resonance and the Habits of Nature, p.272.

- ibid., p. 462.

- Mary Daly, 12th November 1990, GYN/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism, Beacon Press, p.464.

- Sri Isopanishad, 1993, ISKCON, Sri Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Invocation, p.3.